Having discovered the photo of

Taxile Doat so suavely dressed for a photo in his studio, I began to look for photos of other artistic dandies. Here are a few.The first are the Futurists in their bowler hats. Bowlers became a symbol of bourgeois mediocrity but when (

l-r) Russolo, Carra, Marinetti, Boccioni and Severini wore them they were still compatible with their aggressive modernity. Marinetti, a mate of Mussolini, who was another another bowler hat wearer, became a Fascist.

Severini looks like an office clerk on the right of the picture but he scrubbed up well for the opening of his exhibition at the Marlborough Gallery in London in 1913 (

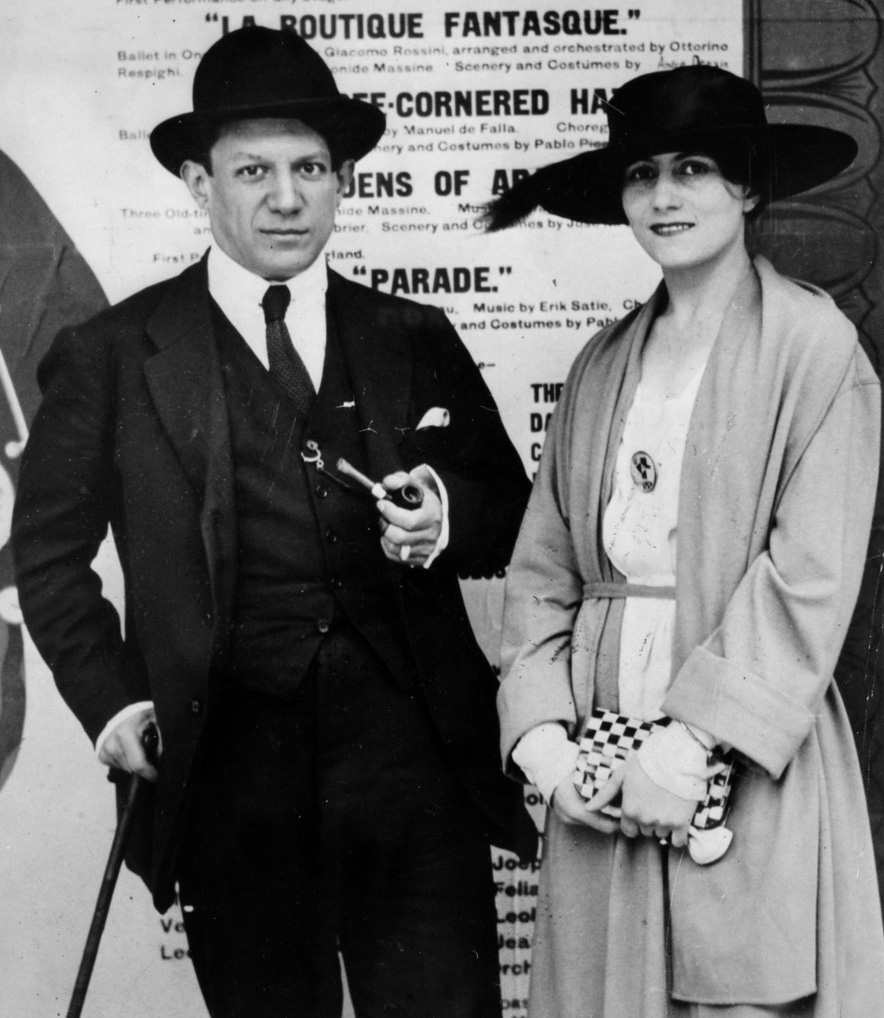

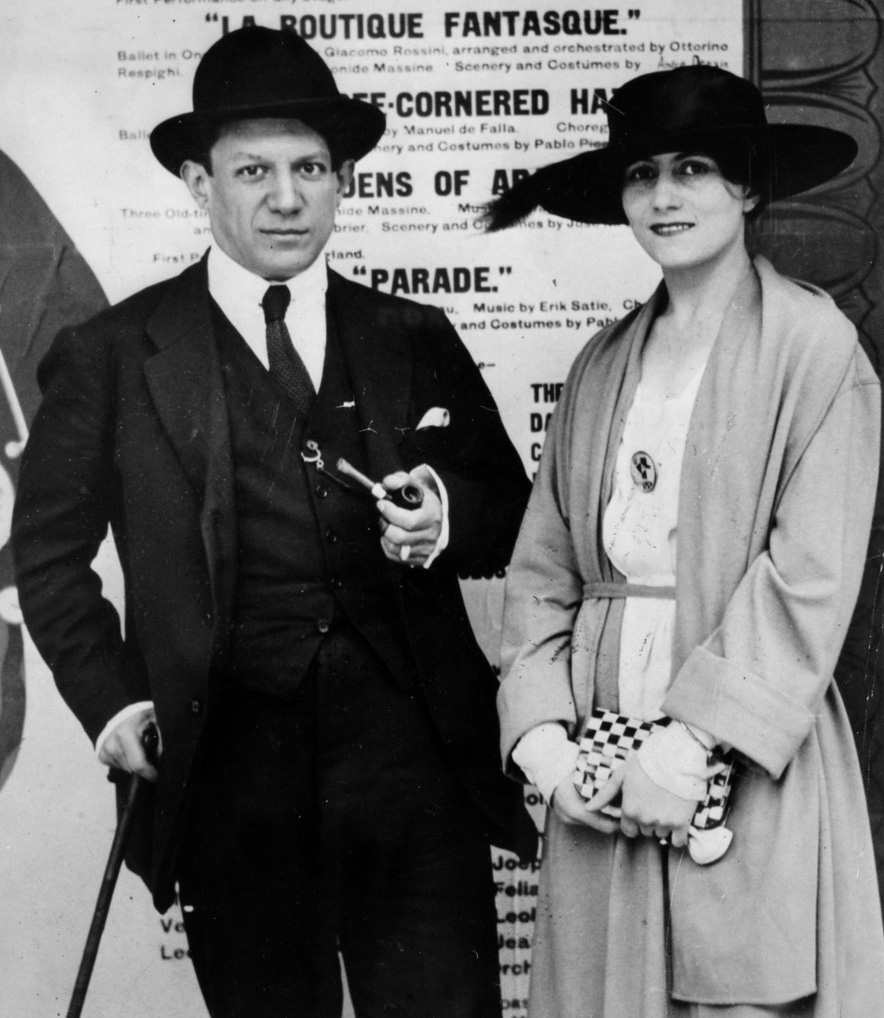

left). At around the same time, Picasso (

below left) was similarly buttoned up, with hat, stick and pipe. He was a cool dresser and pretty well invented the fashion for striped Breton shirts. When he came to England in the 1950s he wore English tweeds but gave them a French accent with a beret (

below right, with Anthony Penrose, "The Boy Who Bit Picasso"). Before the war bow ties and spats might be seen in the studio, as in the picture of Mario Tozzi at the easel (

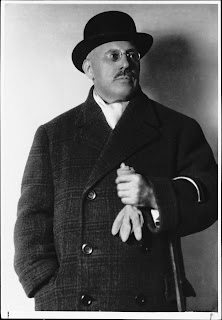

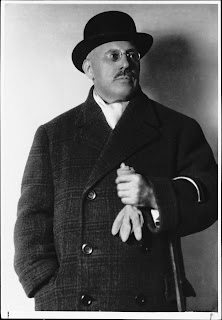

bottom left), but surely Josef Hoffman (

bottom right) couldn't have gone into the studio with that silk scarf and those kid gloves? Right at the bottom there's a picture I've posted before, Isaac Button, the country potter filmed by Robert Fournier in about 1970, by no means a dandy, but a man who, working alone at Soil Hill Pottery near Wakefield, could throw a ton of clay a day wearing a tie - and, you will notice, sufficiently concerned about his clothes to put on an apron over his boiler suit. Don't get the wrong idea about Isaac Button: he and Robert Fournier went to the opera together.

Severini looks like an office clerk on the right of the picture but he scrubbed up well for the opening of his exhibition at the Marlborough Gallery in London in 1913 (left). At around the same time, Picasso (below left) was similarly buttoned up, with hat, stick and pipe. He was a cool dresser and pretty well invented the fashion for striped Breton shirts. When he came to England in the 1950s he wore English tweeds but gave them a French accent with a beret (below right, with Anthony Penrose, "The Boy Who Bit Picasso"). Before the war bow ties and spats might be seen in the studio, as in the picture of Mario Tozzi at the easel (bottom left), but surely Josef Hoffman (bottom right) couldn't have gone into the studio with that silk scarf and those kid gloves? Right at the bottom there's a picture I've posted before, Isaac Button, the country potter filmed by Robert Fournier in about 1970, by no means a dandy, but a man who, working alone at Soil Hill Pottery near Wakefield, could throw a ton of clay a day wearing a tie - and, you will notice, sufficiently concerned about his clothes to put on an apron over his boiler suit. Don't get the wrong idea about Isaac Button: he and Robert Fournier went to the opera together.

Severini looks like an office clerk on the right of the picture but he scrubbed up well for the opening of his exhibition at the Marlborough Gallery in London in 1913 (left). At around the same time, Picasso (below left) was similarly buttoned up, with hat, stick and pipe. He was a cool dresser and pretty well invented the fashion for striped Breton shirts. When he came to England in the 1950s he wore English tweeds but gave them a French accent with a beret (below right, with Anthony Penrose, "The Boy Who Bit Picasso"). Before the war bow ties and spats might be seen in the studio, as in the picture of Mario Tozzi at the easel (bottom left), but surely Josef Hoffman (bottom right) couldn't have gone into the studio with that silk scarf and those kid gloves? Right at the bottom there's a picture I've posted before, Isaac Button, the country potter filmed by Robert Fournier in about 1970, by no means a dandy, but a man who, working alone at Soil Hill Pottery near Wakefield, could throw a ton of clay a day wearing a tie - and, you will notice, sufficiently concerned about his clothes to put on an apron over his boiler suit. Don't get the wrong idea about Isaac Button: he and Robert Fournier went to the opera together.