|

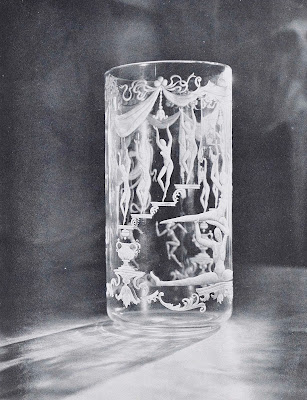

| Designed by Keith Murray, made by Thomas Webb and Corbett |

I have been reading about the series of exhibitions in the 1930s put on to improve standards of industrial design and to increase sales of British industrial goods.

There is a long history of attempts to improve design standards and to bring together artists and manufacturers. As early as the 1830s fears that continental design was outstripping British design led to the creation of government schools of design. The Great Exhibition was the occasion for further hand-wringing. By the end of the century, after the design schools had sunk into an arid syllabus of laboured drawing, they were reformed to offer students craft-based training. But even after these reforms the Royal College of Art was seen to be failing industry by producing craftsmen who could only make luxury goods in ateliers.

|

| Designed and made by Susie Cooper |

By the 1930s the terms of debate had changed. Now the tasks at hand were the modernisation of industry, the need for standardisation, international competitiveness and the problems of mass unemployment. Herbert Read and Walter Gropius doubted the relevance of the crafts, but many hoped the crafts might contribute to mass production.

|

| Designed by A. E. Harvey, made by Hukin and Heath |

One of the key exhibitions in the series was the 1935 Exhibition of British Art in Industry, put on by the Royal Academy and the Royal Society of Arts. It was sponsored by the King and Queen, had a vast infrastructure of the great and the good, a committee of titled individuals, a general committee of notables, an executive committee and numerous trade advisory committees. I have been looking through the attractive souvenir publication, which gives an idea of the contemporary consensus on good design and shows some interesting products, which I've illustrated here.

The preface says: “The machine has opened up a new world of production unknown in the days of handicraft. Hand craftsmanship, of course, has its advantages. It can give individuality, character and charm which the machine by its very nature could not attempt to produce. For over half a century there has been a struggle for supremacy between the rival schools of thought thus created. Experience has proved both to be right and both to be wrong. Many attempts have been made, abroad, to exhibit the ideal combination of both methods ... .”

|

| Designed by Professor R. Y. Gleadowe, made by Wakely & Wheeler with G. T. Friend (engraver) for the Goldsmiths and Silversmiths Co. Ltd. |

The items selected give the impression of cautious modernism, streamlined forms and simple, elegant ornamentation.

A running theme in these debates was public taste, which was thought to be in need of improvement. Designers also thought that manufacturers' taste should be educated. The uncomfortable thought behind these ideas, lightly disguised as the notion of fitness for purpose, was that the public didn't know what was good for them and needed a design elite to tell them. But functionalism and fitness for purpose were eventually debunked by David Pye, who demonstrated that the final form of an object is shaped by aesthetic and not practical decisions. Many still admire the kind of things in the Exhibition of British Art in Industry, but most would accept that taste is a personal matter, and there are now fewer patronising lectures about good design.

No comments :

Post a Comment