30 November 2016

THE KENZAN BRAND OF PAINTED POTTERY

The painted ceramics of Ogata Kenzan (1663–1743) are elegant and harmonious. They match shape to decoration beautifully and they render natural motifs fluently in an almost abstract way. They are so revered in Japan and the West that there is almost a cult of Kenzan.

Bernard Leach worked in the Kenzan tradition and his occasional brush decoration is good because he was trained to draw before he learned pottery. Potters in the Anglo-Oriental tradition shared Leach's admiration of Japanese ceramics but their painting is perfunctory because they doubted the validity of decoration and colour.

Given the beauty of Kenzan's pots, it's disappointing to discover how much in the Kenzan cult is bogus. Ogata Kenzan made very little himself and he commissioned most "Kenzan" pots from unknown potters and painters. Kenzan is a brand rather than a person, like Gucci or Louis Vuitton. Ogata's successors may be presented as traditional craftsmen but some of them were urban sophisticates who ran factories making products for Tokyo department stores.

Leach mythologized his relationship with Kenzan, emphasising what he learned from Urano Shigekichi, whom he called "Ogata Kenzan", and obscuring his debt to other teachers. Leach's supposed inheritance of the Kenzan title was really no more than a certificate of competence from Urano, which, at the suggestion of Tomimoto Kenkichi, he inflated as a way of marketing his work in Japan. Janet Leach said that Tomimoto's idea so went to her husband's head that he came to believe that he was a Kenzan.

Kenzan may be imagined as a traditional pottery workshop without division of labour, but such workshops are not so much a fact as an idea. As soon as pottery-making moved out of the household, there was a division of labour. Excellence in making became possible only when potters specialised in making, decorating or kiln-firing. The studio pottery workshop in the West was a product of the Arts and Crafts philosophy, of which Leach was a late and passionate adherent. Even in the workshop of the English country potter, another of the studio potter's inspirations, there was a division of labour, and admired country potters like George Curtis and Isaac Button were found to be working alone only because by that time they were old and were running down their businesses.

Leach's famous essay "Towards a Standard" in A Potter's Book (1940) is a re-statement of the Arts and Crafts philosophy with all of William Morris's suspicion of industry and idealization of the peasant. The Arts and Crafts movement was influential in Japan as well, and Leach's Japanese colleagues, Tomimoto and Soetsu Yanagi were thoroughly familiar with Ruskin and Morris. And so Leach's "Japanese" ideas were already westernized before he picked them up.

The value and scarcity of work from Ogato Kenzan's workshop inevitably encouraged forgeries. By the early 1960s a large number of them had come onto the market and for a time they deceived collectors and critics. Leach never ceased to believe in them, even after everyone else was undeceived. Although his failing sight made it difficult for him to see them properly, he said that he knew in his heart that they were genuine.

Nevertheless, the best Kenzan ceramics (whether made by Ogata or not) remain an inspiration to pottery painters.

Richard Wilson, The Potter's Brush (Washington: Smithsonian, 2001)

Bernard Leach, Kenzan and his Tradition (London: Faber & Faber, 1966)

28 November 2016

FERRONI'S "THE SUPPER AT EMMAUS" IN SANTA MARIA DI MONTESANTO

| The Supper at Emmaus, Riccardo Ferroni |

There's a third Santa Maria in the Piazza, Santa Maria di Montesanto, the twin of Santa Maria dei Miracoli, and it has a surprising painting, The Supper at Emmaus, by Riccardo Tommasi Ferroni.

It looks like a conventional Baroque painting until you notice that the boy in the foreground is wearing trainers. Then you notice that Jesus has put the meal on a newspaper. Ferroni painted it in 1982. It's a rare setting of a biblical story in a quasi-contemporary setting, which interested me because in my narrative ceramics I tried something similar.

Ferroni (1934-2000) was born into an artistic family and studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Florence. Later he moved to Rome. By the end of the 1950s he was recognized as a modern painter in the school of Caravaggio, referring to pictorial forms of the past, in particular Mannerism and the Baroque. He he participated in the Fourth Quadrennial in Rome (1965) and in the Fourth Biennial of Contemporary Art in Paris. In 1982 he was elected to the Accademia di San Luca and exhibited at at the Venice Biennale, where he was involved in an altercation with Antoni Tàpies.

|

| Self-Portrait with Verdi, Riccardo Ferroni |

|

| Caravaggio, Judith Beheading Holofernes |

25 November 2016

STIG LINDBERG'S CERAMICS AND BIOMORPHIC DESIGN

|

| Faience vases by Stig Lindberg (1950s) |

Lindberg studied at the Swedish State School of Arts, Crafts and Design in Stockholm, with the intention of becoming a painter. He started at Gustavsberg in 1937 and became their art director in 1949. He remained with the company until 1980, when he retired to Italy to set up his own studio. Much of his work was in faience, painted tin-glaze, in which he made a modernist re-interpretation of an old method of decoration, like these vases from the 1950s (above). His faience designs were painted directly in-glaze, an expensive method of decoration also used, in a similar medium, by the Poole Pottery in Dorset.

In the 1950s, many of Lindberg's forms were derived from biomorphism, a movement in painting and sculpture that evoked living forms but was generally non-representational. The most consistent exponent of biomorphism was Hans Arp (below). Many of Miró's forms were biomorphic too.

|

| Hans Arp, Human Concretion (1933) |

Henry Moore and Barbara Hepworth produced biomorphic sculptures - Moore's representational, Hepworth's (below) abstract. In the post-war period biomorphism heavily influenced the applied arts.

|

| Barbara Hepworth, Corinthos (1954) |

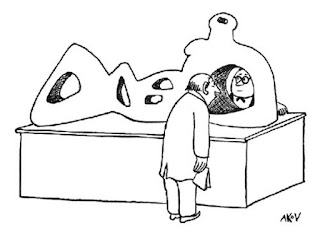

Because of the diffusion of biomorphism into interior design it became emblematic of modernism. There were cartoons of puzzled museum visitors looking through holes in biomorphic sculptures – Anatol Kovarsky's classic (below) was published in The New Yorker in 1947.

|

| Anatol Kovarsky, The New Yorker (1947) |

But the puzzled visitor went home and used biomorphic glassware, biomorphic ceramics like Lindberg's, textiles with biomorphic motifs and even biomorphic furniture (below)

| Murano glass (1950s) |

|

| Textile by Robert Stewart (1950s) |

|

| T.H.Robsjohn Gibbings cocktail table (1950s) |

20 November 2016

MODERNIST CERAMICS BY PICASSO, MIRÓ, LURÇAT AND THE BAYSWATER THREE

Newland’s papers in the Central Saint Martins archive record much of this period. He was training art teachers at London’s Institute of Education, many of whom were inspired by Picasso’s ceramics. There was an enthusiasm for ceramics in schools, which equipped pottery studios, and education authorities sent round traveling exhibitions of pottery to inspire the pupils.

Newland's enthusiasm for brightly-painted European pottery represented a counter-current to Bernard Leach's muted pottery inspired by the country wares of England and Japan. “It wasn’t that we were anti-Leach,", said Newland, "it’s just that we had other things to do.” But reading his papers, you detect his irritation with Leach, whom he regarded, with some justification, as pretentious and full of himself. He mentions the exhibition of Ceramics in the Home, organised in 1951 by The Observer newspaper that showed work by Newland, Vergette and Hine, Hans Coper and Lucie Rie. Leach wasn’t included. That annoyed him, said Newland, and he kicked up a fuss with his MP. At that point that Leach dismissed the others as “Picassoettes”.

Newland says that they could just as well have been be called Miróettes, because Picasso was only one of their influences. Many other continental artists had turned to pottery at that time, Miró (above), and Lurçat (below) in particular.

One artist not mentioned by Newland was Gino Severini. I didn’t know he had worked in ceramics until I saw this piece (below) in a shop in Cortona, his birthplace. It's painted in overglaze colours on blanks which had been made in a factory. Severini is well known as one of the original Futurists, the iconoclastic artists who grouped themselves around Marinetti, but he had a much longer career post-Futurism, and worked in several media. Not surprisingly he tried ceramics as well.

There is renewed interest in the artistic ceramics of this period. Some of it is interesting rather than good, but much of it is good as well as interesting, an attempt to create a modernist art pottery that doesn't look back sentimentally towards rural and pre-industrial forms.

18 November 2016

PAINTED POTTERY BY ALFRED AND LOUISE POWELL

A sugar bowl by Alfred and Louise Powell for Wedgwood, 1920s.

Alfred trained as an architect, Louise as an embroiderer and a calligrapher. Alfred persuaded Wedgwood to revive the art of freehand painting on pottery, one of the most successful marriages of Arts and Crafts ideas with industrial manufacturing, lasting until the late 1930s. The Powells worked at Wedgwood's factory in Stoke-on-Trent and also had a small studio in London where blank Wedgwood pottery was sent for decoration.

Alfred Powell was invited by W.R.Lethaby to start a pottery painting class at the Central School of Arts and Crafts in 1906. He only led it for a couple of years and then handed it over to one of the young women in his London studio, Margaret Hindshaw. For twenty years Miss Hindshaw's students produced pottery decorated freehand like this sugar bowl, then her assistant, Dora Billington, acquired a high temperature kiln for the class, and it turned to the Anglo-Oriental style stoneware pottery that was coming into the art galleries under the influence of Bernard Leach and William Staite Murray.

The work designed by the Powells for Wedgwood (much of it decorated by themselves) was the last flowering of the "art pottery" that came out of the Arts and Crafts Movement. William Rothenstein, director of the Royal College of Art, considered the Powells to be the most outstanding pottery decorators of the age and wanted to bring them in to teach in his pottery department. The plan never came off and he became enamored of the bold, textured stonewares of Staite Murray and brought him in instead.

Surface decoration went out of fashion in studio pottery, though it was continued by unfashionable studio potters like those of the Bloomsbury Group, Venessa Bell (above), Duncan Grant and later Quentin Bell. Their making was clumsy and their mark-making lacked fluency, but their sense of design and colour was acute and the relationship between form and decoration on their pots was second to none. Quentin Bell went to the Central School to learn pottery in the 1930s, where he was taught to throw by Miss Billington.

Despite her admiration of the newly fashionable stonewares, Miss Billington continued to decorate with a long flexible brush and later encouraged Alan Caiger-Smith (above) to decorate in this way on white tin glaze. Caiger-Smith revived this tin glaze technique and over fifty years at his Aldermaston pottery trained dozens of young potters. One of them was Judith Partridge. I trained with Judith Partridge in the 1970s. So that's why I like this sugar bowl.

Alfred trained as an architect, Louise as an embroiderer and a calligrapher. Alfred persuaded Wedgwood to revive the art of freehand painting on pottery, one of the most successful marriages of Arts and Crafts ideas with industrial manufacturing, lasting until the late 1930s. The Powells worked at Wedgwood's factory in Stoke-on-Trent and also had a small studio in London where blank Wedgwood pottery was sent for decoration.

Alfred Powell was invited by W.R.Lethaby to start a pottery painting class at the Central School of Arts and Crafts in 1906. He only led it for a couple of years and then handed it over to one of the young women in his London studio, Margaret Hindshaw. For twenty years Miss Hindshaw's students produced pottery decorated freehand like this sugar bowl, then her assistant, Dora Billington, acquired a high temperature kiln for the class, and it turned to the Anglo-Oriental style stoneware pottery that was coming into the art galleries under the influence of Bernard Leach and William Staite Murray.

The work designed by the Powells for Wedgwood (much of it decorated by themselves) was the last flowering of the "art pottery" that came out of the Arts and Crafts Movement. William Rothenstein, director of the Royal College of Art, considered the Powells to be the most outstanding pottery decorators of the age and wanted to bring them in to teach in his pottery department. The plan never came off and he became enamored of the bold, textured stonewares of Staite Murray and brought him in instead.

Surface decoration went out of fashion in studio pottery, though it was continued by unfashionable studio potters like those of the Bloomsbury Group, Venessa Bell (above), Duncan Grant and later Quentin Bell. Their making was clumsy and their mark-making lacked fluency, but their sense of design and colour was acute and the relationship between form and decoration on their pots was second to none. Quentin Bell went to the Central School to learn pottery in the 1930s, where he was taught to throw by Miss Billington.

Despite her admiration of the newly fashionable stonewares, Miss Billington continued to decorate with a long flexible brush and later encouraged Alan Caiger-Smith (above) to decorate in this way on white tin glaze. Caiger-Smith revived this tin glaze technique and over fifty years at his Aldermaston pottery trained dozens of young potters. One of them was Judith Partridge. I trained with Judith Partridge in the 1970s. So that's why I like this sugar bowl.

15 November 2016

SHAPING CERAMICS: FROM LUCIE RIE TO EDMUND DE WAAL

In a ground-breaking exhibition, “Shaping Ceramics: From Lucie Rie to Edmund de Waal”, the Jewish Museum London shows the impact on studio pottery in Britain of Jewish artists who fled Nazi Europe. Lucie Rie, Hans Coper, Grete Marks and Ruth Duckworth brought a modernist aesthetic to the craft. The exhibition also shows the work of ceramists who express in one way or another their relation to their Jewish heritage: Dan Arbeid, David Breuer-Weil, David Cohen, Janet Haig, David Jones, Antonia Salmon, Ray Silverman, Jenny Stolzenberg and Edmund de Waal. A review follows later.

Jewish Museum London

Raymond Burton House

129-131 Albert Street

London NW1 7NB

Subscribe to:

Posts

(

Atom

)