25 September 2017

BRYAN MAGEE'S HOXTON CHILDHOOD

Wandering through the streets of Hoxton made me pick up Bryan Magee's childhood memoir Clouds of Glory: A Hoxton Childhood. He is blessed with a sharp memory - he said that until the age of nineteen he remembered everything he had read, which helped him from his working-class environment into Oxford - and his book is an extraordinarily vivid record of Hoxton in the 1930s. It is well written and probably one of the best childhood memoirs you will find.

Magee lived at the top end of Hoxton Street, near the canal, behind his father's menswear shop. From about the age of three he lived much of his life in the streets, many of which he describes in detail. Being in the tailoring trade, his father came into contact with many Jews, with whom he was on good terms, and some of his business associates taught Bryan scraps of Yiddish, which he has since forgotten. His father hated the fascists. Because he was dark, smartly-dressed and had a big nose a gang of them tried to beat him up in the street.

I knew Magee when he was the Labour MP for Leyton around 1980. He never seemed to fit into the Leyton Labour Party, he was too smooth and too intellectual. He announced his defection to the SDP to the Leyton party and calmly walked out of a meeting that had burst into uproar around him.

He appeared too well dressed, in a banker's overcoat and a good suit. He never carried a briefcase or anything, and when he gave his monthly report he took a single sheet of notes from his breast pocket. To people who said he was a toff and a snob he said that he had a working-class upbringing. I found it hard to believe until I read this book, which, as well as recording the vanished life of Hoxton, explains much about himself.

His father prided himself on the sale of good quality clothes and took trouble to find them. To advertise his trade, he was always well-dressed himself, and that's obviously where Bryan inherited his taste for good suits. Magee senior used to measure customers and send the measurements to Jewish tailors. Bryan was his messenger and had to collect the suits, which were wrapped in a brown paper parcel and carried back through the streets. He hated this job and records that ever since he has hated carrying things about with him, hence no briefcase.

24 September 2017

MORE HOXTON SIGNS

|

| Metropolitan Borough of Shoreditch, abolished 1965 |

Yesterday I walked from the Geffrye Museum to Old Street via Falkirk Street, further north than previously, where the smart restaurants and designers have hardly reached, an area of public housing and local shops. City landmarks including The Shard can be seen between the flats. Most of the area was built after the war, either following bombing or slum clearance. (By the 1970s conservationists were complaining that the GLC destroyed more housing than the Luftwaffe).

Signage is everywhere so I had to make a rule about what to include and what to ignore. The No Parking sign by the Metropolitan Borough of Shoreditch gave me a cut off of 1965 when the borough was abolished and Hackney was created. Otherwise the lettering had to be visually appealing or historically significant.

|

| Haberdasher's Place was destroyed by enemy action and rebuilt in 1952, the lettered plaque laid by the Master of the Worshipful Company of Haberdashers. |

The connection with the Worshipful Company of Haberdashers dates from Robert Aske (1619-1689), the prosperous merchant who owned land in Hoxton and bequeathed his estate to the Company. The first Haberdashers Aske's school was here.

|

| Many London County Council blocks of the 'thirties to the 'fifties are identified in these elegant Roman capitals. |

|

| The products offered identify this sign as recent, but I had to include it. |

|

| This lettering, popular on pubs around 1900, was adapted for print by the Stephenson Blake type foundry as their Windsor typeface in 1905. |

23 September 2017

HOXTON SIGNS

|

| "E pulveri lux et vis." From the dust, light and power. They generated electricity by burning rubbish. |

I’m exhibiting with fifty potters in Ceramics in the City at the Geffrye Museum as part of London Design Week and today I walked back to Old Street station through Drysdale Street, Hoxton Street, Coronet Street and Brunswick Place. The attraction of Hoxton is the modern, design-led businesses in an industrial setting with varied and curious buildings recalling the area’s past trades. The actual purpose of the old buildings isn’t always obvious but some of them still have their names in carved stone, brick or tiles. The lettering is interesting , and I like old fascias and signs like this. Here are a few I saw on my way.

|

| Still Shaftesbury House but no longer the Hoxton Market Christian Mission |

|

| Gill Sans numbers and tesserae painted over. |

|

| The Alexandra Trust Dining Rooms, built by tea magnate Sir Thomas Lipton, to offer "very cheap meals to the poor working classes." |

|

| One of Passmore Edwards' many libraries. |

|

| The Hop Pole. Well-preserved lettering from c.1890. |

|

| The Leysian Mission, a large Methodist initiative begun by Cambridge students. Now apartments. |

22 September 2017

HAMADA AND LEACH AT THE JAPANESE EMBASSY

The Japanese embassy has an exhibition of ceramics by Shoji Hamada, Bernard Leach and some of their early pupils, put on to celebrate the friendship between Mashiko, where Hamada had his studio, and St Ives, where they came in 1920 to start the Leach Pottery, Mashiko: Imagined in the UK. The relationship between the towns remains strong, Mashiko town contributing two million yen to the restoration of the Leach Pottery a few years ago.

We went to the exhibition launch on Wednesday, where the main speakers were Tomoo Hamada, Shoji’s grandson, and Rupert Faulkner, senior curator, Japan, in the Asian department of the V&A.

Leach, as we know, had a mission to bring together East and West, combining the best of both cultures, and the Eastern influence on his pottery is familiar, but the speakers made it clear that there was traffic the other way as well. Leach's Japanese milieu in the second decade of the 20th century was infused with ideas from Ruskin and Morris and there has been appropriation in Japan of English craft objects and methods, such as rush-bottomed chairs and the English method of making handles on pots, with a loop if clay at the side rather than a loop of bamboo on the top.

18 September 2017

LAWN ROAD FLATS

Yesterday we visited Isokon, the Lawn Road Flats in Hampstead, built in 1934 by Wells Coates, which was part of the Open House weekend in London. Three of the residents invited us in. The flats were designed for busy professionals who wanted an uncomplicated life, very small with tiny kitchens originally provided with one hotplate and a grill, so you couldn’t eat much more than beans on toast. There was a restaurant but it turned out that residents weren’t quite ready for that degree of collectivisation and it was replaced by a bar, designed by Marcel Breuer. The flats were intended to be fit for purpose, to discourage excessive consumption and to spearhead social reform. Among the early tenants were Breuer, Walter Gropius, László Moholy-Nagy and Agatha Christie - I like to imagine the conversation between Gropius and Christie. They also had, over the years, a disproportionately large number of Soviet spies.

Jack Pritchard, the owner and developer, worked worked for Venesta, the Estonian plywood company, and specified extensive use of plywood, including walls, floors and furniture. Gropius was the design director of the Isokon company which was set up to produce the furniture. Some of the Lawn Road fittings are currently on loan to the V&A’s Plywood exhibition.

It was interesting to hear that this modernist Grade I listed building is uncomfortable to live in, cold and damp in the winter. Public housing similarly constructed in the ‘sixties and ‘seventies was notorious for damp and condensation. Design and construction have moved on and the Lawn Road Flats are really a museum.

Isokon Plus produces some of the original designs that were made for Lawn Road. The the original Isokon company was committed to standardisation of parts, rationalisation of process and methods, and modern industrial design based on the principle of conspicuous economy, all of which imply low cost, but Isokon products are very expensive now - the famous Isokon Penguin Donkey, for example, is £670. This is conspicuous consumption and runs counter to ideas of producing simple, well-designed products that everyone can afford. The baton has been picked up by Ikea where you can buy comparable products at a tenth of the price.

15 September 2017

GORDON BALDWIN IN STOKE-ON-TRENT

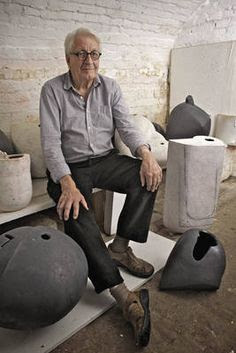

|

| Gordon Baldwin |

Gordon Forsyth, who I wrote about yesterday, was well-known to Dora Billington, who taught at the Central School of Arts and Crafts for thirty-five years and who is also famous for her sympathies with factory pottery; but she had an ambivalent attitude towards her home town of Stoke-on-Trent and I don't believe she ever worked there after leaving Hanley art school in 1912. Nevertheless, after the second world war she made a term in The Potteries a compulsory part of the course at the Central.

Gordon Baldwin told me about his experience as one of Billington’s students. “We all had a sort of down on what had gone on in Stoke-on-Trent,” he said. “We were breaking free of Leach, we were breaking free of Stoke-on-Trent, doing all manner of things.” But he enjoyed his term at Burslem art school, visiting potteries, finding out about industrial techniques, sitting in in with paintresses, learning rosebud painting and how to put on transfers, all of which he used in a different way.

14 September 2017

GORDON FORSYTH: "20th CENTURY CERAMICS"

László Hradszki posted a picture on Facebook of a tile by István Gádor with a leaping horse that he'd bought recently. As it happens, I'd been looking at another picture of this tile (above) (or, more likely, another cast from the same mould) in Gordon Forsyth’s book 20th Century Ceramics, published by The Studio in 1936.

20th Century Ceramics is a good account, one of the best ever written, because it's an even-handed survey of both factory and studio pottery and it covers studio pottery from around the world in an impartial manner. Forsyth was principal of the Stoke-on-Trent schools of art and a fine designer, known particularly for his decorations in lustre for Pilkington, rather in the style of William de Morgan.

The book covers pottery from Britain, the USA, Austria, China, Denmark, France, Germany, Holland, Hungary, Italy, Japan, Poland, Sweden and Switzerland. It's good on Hungarian and Italian potters. The Hungarians are Gádor, Géza Gorka, Margit Kovács and Lili Márkus. I was interested to see some of Kovács’s vessels (above), as she is known mainly for her sculpture, but these vessels are decorative pieces rather than tableware. Forsyth shows a bias towards studio pottery in his coverage of the continent, unlike his excellent coverage of the best British factory pottery, and there is nothing from the well-known factories of Herendt or Zsolnay. The Italian potters are Guido Andlovitz and others of the Società Ceramica Italiana, Dante Baldelli, the Cantagalli pottery, Industria Ceramica Salernitana, Giuseppe Mazzetti, Ugo Zaccagnini and others of the Monteolivito pottery, Mario Morelli, Gio Ponti, Ricardo Ginori, and Luigi Zortea. From Austria, there is pottery made by Lucie Rie (below) before she left for London.

Forsyth occupied that thought-provoking position between factory and studio pottery and he expressed views that were common in the 1930s:

"A wholly artificial gulf has been created between the studio potter and the large-scale manufacturer. Sometimes studio pottery is dismissed as being ineffective "Art and Crafty" productions, technically defective. This is in the main wholly erroneous and unjust criticism of studio potters, but it is equally erroneous for studio potters to think that all manufacturers are Philistines and only concerned with commercial and technical success.

"We feel very strongly that progress in industry has been considerably retarded by unbalanced enthusiasts on both sides, and the time has now arrived for co-operation between the individual experimenter and his collaboration with large-scale producers. The position at the moment is that all such stupid prejudice that has hitherto kept artists and manufacturers apart should be immediately dropped, and that industrialists must find a solution of the problem of incorporating the best artists that can be found and bring them into industry.

"Many of our first-class studio potters who at present are having a struggle as individual manufacturers could be well employed within mass production concerns without loss of their own individuality or lowering their own ideals, and with far larger scope and far greater security than they at present enjoy. We look forward to the time when there will be no gulf between the studio potters and the manufacturers."

13 September 2017

MARIANNE BRANDT'S TEAPOT

|

| Marianne Brandt, 1929, with jewellery for a metal party at the Bauhaus |

I decided to find out more about Marianne Brandt’s geometrical metal teapot, which I used to illustrate a recent post. It looks “functional” (i.e. plain) but I wondered whether it worked as a teapot. Whether it does or not, it has become an icon of the Bauhaus (where it was made) and, by extension, of a rational approach to manufacturing, food preparation and domestic life. I said that it was aggressively original and it may be seen as the image of a teapot, the realisation in three dimensions of a Constructivist poster (below), rather than a teapot that you can actually make tea in.

|

| El Lissitsky's poster, "Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge," 1919 |

Brandt produced it when she was a student in the metal workshop at the Weimar Bauhaus, where she studied under Moholy-Nagy, whose appointment in 1923 marked a change from the Bauhaus’s original craft ideology to an ideology of mass production. But Brandt’s first version, now in the British Museum (BM), is still visibly a craft object, with hammer marks on its curved surface. Judy Rudoe of the BM says that the Bauhaus had little experience of designing for industry at this stage.

|

| Brandt's iconic teapot |

Brandt was born in Chemnitz in 1893 and she trained as a painter before joining the Bauhaus, where it was unusual for a woman to study metalwork. She was Moholy-Nagy's star pupil and after he left she took over from him as metalwork leader. She later worked for Gropius in private practice and then for the Ruppel metal goods factory in Gotha, a curious appointment because Ruppel were old fashioned, but Brandt rationalised their product range and introduced new, radical designs (below). Like Moholy-Nagy she later turned to photography. She remained in the east and her later career was in art education, compromising with the Nazis and the Communists, both of whom had contempt for the Bauhaus.

|

| Marianne Brandt: clock designed for the Ruppel metalwork company |

Because Brandt became a decisive and influential industrial designer after her experiments at the Bauhaus, scholarly authors like Brockhage and Lindner are said to pay little attention to her early work, but their publishers still put the iconic teapot on the cover of their monograph.

12 September 2017

HABITAT TEAPOTS

|

| Kristina |

I was right to be reminded by Ladislaw Sutnar's 1929 tea set, which I mentioned in my last post, of Habitat in the 1980s, because Habitat did indeed produce a similar teaset, their popular Kristina range, which came with either a pink or a blue rim. Sutnar's was porcelain and Habitat's was earthenware, but they are otherwise similar, even in the shapes of the cups and saucers, so similar that Sutnar may have been the direct inspiration for Habitat's designers. There was also a porcelain range, Sienna (below), without a teapot, that was cheaper than Kristina. The pictures are taken from Habitat's 1983-4 catalogue.

|

| Sienna |

Other Habitat china was inspired by 18th century models - their Old Colonial and Sharon ranges (below) were produced for fifteen or twenty years (I had pieces from both.) You could choose a sleek, modern image from Habitat or a more countrified, cottagey look.

|

| Old Colonial |

|

| Sharon |

11 September 2017

FUNCTIONAL TEAPOTS

|

| A Brown Betty teapot. |

Is this what a functional teapot looks like? The question was prompted by Keith Savage asking me whether the Torquay ware teapot I wrote about recently (below) poured well or whether it was just decorative. It's clean inside and I don't think anyone has ever made tea in it. I'd put it on a shelf and hadn't thought of using it, but when I read Keith's comment I tried it. It does pour well. The flat shape makes it stable, the position of the handle gives a good lift and the spout doesn't drip. It takes half a pint of liquid, two cups.

|

| Aller Vale teapot, c.1920 |

It's not what you think of as a functional teapot - the word suggests the long-established Brown Betty, or perhaps Marianne Brandt's Bauhaus teapot (below), not the ornately decorated Torquay pot made by the Aller Vale pottery. Functional implies that if you design for use, form follows inevitably and there will be little or no ornament. David Pye, late professor of furniture at the RCA, concluded that the idea of function as the quality of an object was incoherent and that a useful object's appearance, though constrained, was not determined by its intended use. The choice of form is aesthetic and there is no design without style. Pye makes you wonder why you didn’t realise these things before he said them. For example, nearly every ceiling is flat and smooth, but flatness and smoothness are not requirements of of a ceiling, they are aesthetic choices. What came to be understood as functional meant a smooth, streamlined shape or economy and cheapness.

|

| Marianne Brandt's Bauhaus teapot, c.1924 |

"When any useful thing is designed", said Pye "the shape of it is in no way imposed on the designer, or determined by any influence outside him, or entailed. His freedom in choosing the shape is a limited freedom, it is true, but there are no limitations so close as to relieve him or the maker of responsibility for the appearance of what they have done."

The ornate Torquay ware teapot, designed at about the same time as Marianne Brandt's teapot, works as well as the Brown Betty and I guess it's a more useful teapot than the Brandt. The Brandt sold for £361,000 at Sothebys New York in 2007. The Torquay pot cost £10 in a charity shop.

Ladislaw Sutnar's simple porcelain tea set (above) lacks the ornamentation of the Torquay pot and the aggressive originality of the Brandt. Except for the cups, which are made for an older style of tea drinking, it's hard to date. It could by Habitat in the 1980s; in fact it was manufactured in Czechoslovakia in 1929-32. It looks as if it works.

|

| Tea set by Ladislaw Sutnar, 1929-32 |

Ladislaw Sutnar's simple porcelain tea set (above) lacks the ornamentation of the Torquay pot and the aggressive originality of the Brandt. Except for the cups, which are made for an older style of tea drinking, it's hard to date. It could by Habitat in the 1980s; in fact it was manufactured in Czechoslovakia in 1929-32. It looks as if it works.

10 September 2017

NEWS FROM NOWHERE

|

| The V&A facsimile of News from Nowhere |

The V&A and Thames & Hudson have produced a facsimile of William Morris's utopian novel News from Nowhere in a nice edition at a reasonable price. It was written by Morris and printed by him at the Kelmscott Press in 1890 in Golden Type, which he designed himself.

It's one of the great socialist novels and sets out Morris's vision of a world without private property, big industry, poverty, crime or marriage. He had been a political activist in the 1880s, during which time he became less interested in design, but by 1890 he was worn out by the petty squabbles in his Socialist League and by the fanatics who were only interested in him for his money. The Kelmscott Press was his last venture, into which he poured most of his energy.

|

| From the British Library scan |

News from Nowhere has a charming quasi-medieval look. The British Library scan of the original edition shows the typeface very clearly (above). Although pretty, it is not very legible. It's too black and there isn't enough contrast between thick and thin strokes. John Lewis and John Brinkley (Graphic Design, 1954) say that, in designing it, Morris took Nicholas Jensen's 15th century Venetian typeface (below), gothicized it and trebled its weight.

|

| Nicholas Jensen's typeface, 1476 |

“To more than one version of this very black typeface," they say, "he designed and cut on wood rich borders of entwined leaf and flower forms. He had a rough rag paper made, and with a clean but heavy impression he printed his books, which were bound in vellum and tied with silk ribbons. His greatest printing achievement was the folio Chaucer, with decorations by Burne-Jones. This monumental work he finished within a few months of his death. The Kelmscott books were completely out of the tradition of European printing. They could not be imitated for they were unique. To the lover of Renaissance typography, they may appear heavy and ugly. Their virtue in our opinion, was in the attention they drew to good workmanship, to careful presswork, to fine materials and to considered design. The principles that Morris established were later to be practised by every typographer and designer of note and in a wider field were to be the keystone for the teaching of the most influential design school of our age, the Bauhaus.”

8 September 2017

KINGSBURY BARN, ST ALBANS

I'm exhibiting with the Dacorum and Chiltern Potters Guild at Kingsbury Barn St Albans, built by St Albans Abbey for threshing in the fourteenth century. It's a wonder of vernacular building, its beauty of form and texture arising simply from the methods and materials employed. I've borrowed the excellent pictures from the Kingsbury Barn website because they're better than any I could take and give a very good impression of the structure. The barn was restored about ten years ago at cost of £1 million.

The Abbey was a major landowner at the time of building and the barn obviously represented a huge capital investment, its size indicating the extent of their lands and the amount of grain they harvested. It's supposed to have been part of the Abbey's programme of attracting farmers after the the Black Death, but the increase in the price of labour gave the peasants confidence and there was a major revolt in 1381, led by William Grindcobbe, whose name suggests that he was a miller with a grudge against the Abbey's monopoly. The revolt focused on the Abbey gatehouse, but I'd be very surprised if the peasants didn't attack the Kingsbury Barn half a mile away.

It's now used for weddings and exhibitions and local residents complain if there's too much noise. Grindcobbe, you have been warned.

6 September 2017

ADOLF LOOS: ORNAMENT AND CRIME

|

| The Müller House, Prague |

After writing about how British design promoters were shy of ornamentation in the 1930s, I thought I ought to go to the ur-text, Adolf Loos’s essay Ornament and Crime (1908). Influential designers and architects are bound to be opinionated but I hadn’t realised quite how opinionated Loos was. The essay was a response to the critics of his landmark Vienna building for Goldman and Salatsch in the Michaelerplatz, designed as one in the eye for the Secession.

Loos said that ornamentation belonged to an earlier stage in cultural evolution and that using it in the 20th century was no longer appropriate. But he said it more forcefully:

"The Papuan tattoos his skin, his boat, his oar, in short, everything that is within his reach. He is no criminal. The modern man who tattoos himself is a criminal and a degenerate. Those who are tattooed but are not imprisoned are latent criminals or degenerate aristocrats. If a tattooed person dies at liberty, it is only that he died a few years before he committed a murder."

“The evolution of culture,” he said, “is synonymous with the removal of ornament from objects of daily use.”

Ornament was wasteful because decorated items soon bored their users, who replaced them before they needed to, and it impoverished the worker because he was not adequately compensated. Ornament “represents a crime against the national economy, and, as a result of it, human labour, men and material are ruined.”

But Loos’s buildings don’t meet the expectations created by Ornament and Crime. They are lavishly finished. In the Müller House in Prague (1928-30) there were few white walls, as there were in some of Voysey's Arts and Crafts houses, which are puritanical by comparison. Surfaces were painted dark green, grey-green, brick red, navy blue and yellow, veneered in mahogany and maple or constructed of travertine and Cippolino marble.

|

| The living room, Müller House |

Loos specified decorations, light fittings, furnishing and pictures. In the living room there is a simple brick and marble fireplace but patterned carpets. He chose Chippendale chairs for the dining room, which has a coffered mahogany ceiling. The Library is also furnished in mahogany, with deep-buttoned Chesterfield sofas and a Dutch tiled stove.

|

| The library, Müller House |

5 September 2017

TORQUAY WARE TEAPOTS

Something quite different from the didactic exhibitions of industrial design I've been writing about recently - a Torquay ware teapot (above). I bought this one from a charity shop today. I'm sure these popular items would have been execrated by the leaders of good taste.

I wrote about Torquay ware in another post, saying that it was made from the local brown clay, was covered in white or blue slip and then decorated, either by scratching through the white to make a line of brown, or by painting with coloured slip. It was made for tourists, who paid sixpence for it, and although it's pretty and cleverly made, the sheer quantities manufactured means it's still cheap in the shops.

Typically, my teapot has a motto round the top in Devon English (below), "Cum me artiez 'elp yersels" Geddit?

It was made by the Aller Vale Pottery, which closed in the 1920s, so it has been kept on a shelf for at least ninety years and well looked after. The "Scandy" pattern (rather like Prince of Wales feathers) on the side was used by many of the potteries in the second decade of the century - they ruthlessly plagiarized one another in search of the holidaymaker's sixpence.

Subscribe to:

Posts

(

Atom

)